Plugging into Orbit

Sending anything into orbit is expensive and complicated. DPhi Space wants to democratize space by offering ridesharing satellites with a simple hardware interface and a lot of computing power. Companies and individuals alike can host their payloads or run their programs in orbit with DPhi’s Satellite as a Service offering.

What do farmers, traders, and tourists have in common? How about urban planners, first responders, and logistics companies? They all use data provided by satellites. Farmers monitor their crops, traders estimate stockpile sizes, and tourists navigate to their hotels. Similarly, urban planners study traffic flows, first responders identify natural catastrophes, and logistics companies track shipping crates across the ocean. From weather forecasts to the Internet of Things, information sent from space down to Earth is the backbone of our daily services.

The number of objects launched into space has soared in recent years, as rockets from companies like SpaceX have lowered the threshold for transporting satellites. Now these satellite passengers are the new bottleneck: gravity-defying companies need months of work and solid space domain expertise to integrate their instruments into a satellite platform that can hop on a rocket.

Similarly, the amount of data collected in orbit has skyrocketed, and data transfer has become another choke point. It takes hours to downlink a satellite image through congested radio antennas set up at oversubscribed ground stations – that is, after you’ve made it to the top of the ever-growing download queue.

Satellite as a Service

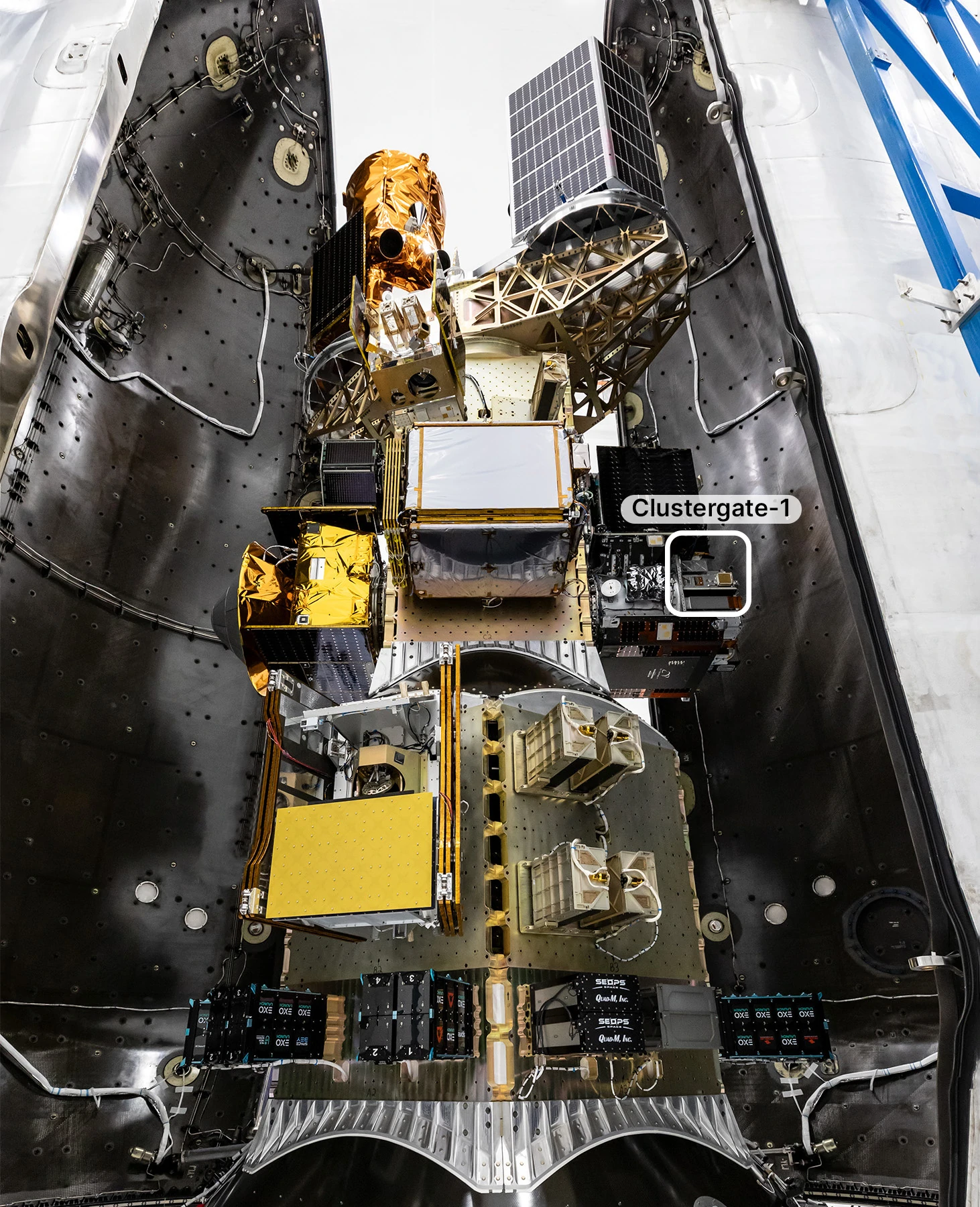

Aziz Belkhiria co-founded DPhi Space to fix these two bottlenecks. The company has developed Clustergate, a container that makes it easy to plug multiple payloads into a satellite and process data on the provided servers. Hardware clients have standard cables to connect to, while software developers see a cloud interface similar to AWS or Azure.

DPhi flew its first mission in March 2025, and its next launch is scheduled for February 2026. In the first mission, DPhi’s Clustergate hitched a ride from another satellite on board a SpaceX rocket. Future liftoffs don’t necessarily need to come from SpaceX, as DPhi is launcher-agnostic. In contrast, the company doubles down on the satellite layer: Aziz says DPhi plans to own the entire satellite in the future. This gives them the freedom to fully optimize the platform for many different users.

The company has roughly three kinds of customers. One group sends cameras and sensors to communicate or observe Earth from orbit, while another sends precision hardware up to test and demonstrate that it survives space conditions. A third customer segment uses DPhi’s onboard computers to process space-based data closer to the source. DPhi has particularly high growth expectations for the software segment.

The amount of time and money customers can save by processing space data in space depends only on how creative their software solutions are, Aziz explains. The better these algorithms are at data triage, the more compact the conclusions. For example, downloading a satellite image of wildfires in Los Angeles will take hours, Aziz calculates. Meanwhile, processing collected images in orbit and sending down only the coordinates and the text “fire” or “no fire” is thousands of times faster and cheaper.

Paying customers convinced skeptical investors

Like many deep-tech founders, Aziz didn’t set out to become an entrepreneur: he simply ran into a real-world problem and saw a path to the solution. While studying microengineering and robotics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, Aziz was also the President of the EPFL Spacecraft Team. In 2023, the students sent a computer named Bunny into space in record time on board a D-Orbit satellite. Yet even with their record-breaking speed, the EPFL team felt that integrating hardware and software into the host satellite took unreasonably long. The cost was also prohibitive: had the lucky students needed to pay the market price for piggybacking a space ride, Bunny would never have hopped off the ground.

Aziz and his three founding team members believed there had to be a better way. And because the four had already worked so well together, they believed they were the right team to find that better way. DPhi Space was incorporated in January 2024; the company graduated Venture Kick in March and joined the Kickfund portfolio in December 2024.

DPhi is very lean for a company operating in space: they launched their first mission with just the core team of four. The company closed its CHF 2.1M pre-seed round only shortly before liftoff, and Aziz says none of that money was used for the hardware: the mission was financed by paying customers. The pre-seed money was, however, needed to keep the company alive long enough to make it to the launch: DPhi was living on the edge of survival, Aziz admits. The first financing round was a tough one to close, he remarks. The space business is deep tech in the extreme: it has long lead times and high upfront costs. And while VCs liked the concept on paper, many envisioned exploding rockets and other sensational ways for a space company to fail.

What eventually convinced the first investors were the paying customers. Since multiple businesses were willing to not only send their precious tools into space aboard DPhi’s Clustergate but also pay for the privilege, DPhi must be a reputable business with a reasonable risk profile. Thanks to both the successful first mission and the successful first financing round, DPhi can now breathe easier. The company has doubled its headcount and bought production machines to professionalize manufacturing. They’ve even insourced some production back from suppliers, Aziz adds, which has made testing and troubleshooting much faster.

Meanwhile, customers are already asking for more frequent launches. As lean and efficient as the team is, eight people are not enough to meet the growing demand. Aziz says that DPhi is planning the next financing round for early 2026, and the team will surely grow fast afterwards. True to his industry’s timelines, Aziz is already designing DPhi’s activities and cost structure in the year 2029 as preparation for the next investor pitches.

Swiss space companies low in the food chain

DPhi might be building hardware, but it thinks in systems: the company’s raison d’être is to absorb all the complexities of satellite integration on behalf of its customers and to create an interface suitable for diverse users. This is not a common business model for Swiss companies operating in space, Aziz muses.

Instead, Switzerland is known for high-precision components that get integrated into larger systems later by companies elsewhere. Granted, working under the prestigious “Made in Switzerland” technology label helps DPhi gain international trust, and Aziz wants to make sure his company’s components deliver on the quality promise. But he also wants to encourage other Swiss space firms to join him higher up the food chain. Aziz does see a transition coming, as many newer startups focus on systems rather than just perfecting smaller parts of the whole.

Founding a company for satellite ridesharing and space computing is probably not the fastest way to make money, Aziz admits; an Earthbound cloud company would surely have been easier to build. Yet the challenge is what motivates the team: like John F. Kennedy, DPhi didn’t choose to go to space because it was easy, but because it was hard. Even the company name declares the vision: to defy space.

None of that means it isn’t good business, though. People used to do all their work on local computers, Aziz remarks. Then, as the internet took off, we moved much of this work into the cloud. This helped us use resources more efficiently and handle much larger volumes of data – and create a trillion-dollar cloud industry. A similar shift in orbit is coming, and space computing will lift off entirely new kinds of products and ideas. This means democratization of space, Aziz celebrates. Soon you won’t need to be a large enterprise or highly specialized deep-tech company to build something in space; small firms, nonprofits and individuals will have just as easy access to orbit – and beyond.

DPhi Space is one of the rising companies mentioned in the Swiss Deep Tech Report 2025. Read more about the report here.